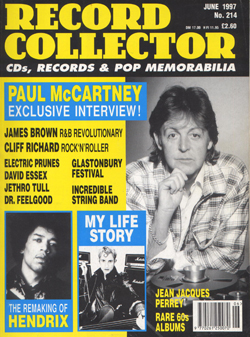

Record

Collector - The Feelgood Factor (juin 1997)

Article de Michael

Heatley © Record Collector (site

internet)

When Dr Feelgood

first hit the beer-stained stages of the London pub circuit in 1973,

few could have dreamed that in just three short years they’d

sit on top of the U.K. LP chart among Abba, Rod Stewart and the

Stylistics. Nobody knew it at the time, but the band’s emergence

signalled a dramatic sea-change in British rock, one which was a

rip a hole through the hull of the increasingly complacent music

industry via punk rock.

Dr Feelgood emerged from two very distinct musical traditions that

had existed for years on Canvey Island, Essex, just waiting to bump

into each other? Their roots stretch back to the early 1960s, a

whole decade before 19-year-old singer Lee Collinson (nicknamed

Brilleaux for his wire-wool hairstyle) and guitarist mate John B.

Sparkes joined forces with guitarist John Wilkinson (alias Wilko

Johnson) and his schoolyard chum, drummer John Martin, to hammer

out R&B music for their own amusement.

Lee Collinson was born in Durban on 10th May 1952. His father was

a lathe operator who had travelled from England to South Africa,

and as a result of the geographical accident of birth Lee had a

Zulu nanny and was able to speak Swahili before he could speak English.

By the time he was four or five, the family had returned to England

where they lived for a while in London before decamping to Canvey

in the mid-1960s. And that was where he encountered Wilko, playing

in an outfit called the North Avenue Jug Band at a carnival talent

contest. "I was about 18 at the time

and he was about 13 or 14, which at that age is a big gap",

Wilko recalls. "I remember Lee having

a very striking personality; he seemed pretty together."

Flattery

Deciding that imitation was

the sincerest form of flattery, Lee, Sparko and Chris Fenwick (later

the Feelgood’s manager) hit the streets of Canvey in 1967

busking as the South Side Jug Band. "It was Lee’s idea

to form a jug band", recalls Sparko. "He’d

invented this eight-string guitar which was tuned like a banjo.

We used to stay in one of the caravans over weekends and then go

busking in pubs all over Kent." The

outfit, which later mutated into the Pigboy Charlie Blues Band,

used to move their home-made equipment around in an adapted pram.

Wlko had meanwhile left Canvey to obtain a degree, after which he

hit the hippie trail to India. On his return, he ran into Lee. "He

started telling me about this ban and how the guitarist had just

left", Wilko remembers. "I

though I’d like to play, but he didn’t have the bottle

to ask me and I didn’t have the bottle to ask him."

A short while later his lieutenant Sparko turned up on Wilko’s

doorstep and just said, "Do

you want to join our band ?"

To honour the newcomer, the band immediately took a new game from

the old Pirates song "Dr Feelgood", originally a hit for

William "Piano Red" Perryman and already a popular part

of their repertoire. When Chris Fenwick, now a drama student, was

invited to a wedding in Holland, he returned to England with the

promise of a few paid gigs. The only fly in the ointment was the

lack of a full-time drummer - and it was at this point that Wilko

suggested John Martin, alias "The Big Figure", whom he’d

played with in the Roamers.

The final leg of their apprenticeship came in the form of an alliance

with Heinz Burt, a former member of the Tornados of "Telstar"

fame. With his distinctive blond quiff, he’d managed a couple

of solo hits in "Just Like Eddie" and "Country Boy",

both in 1963. The younger Feelgoods saw Heinz as an experienced

hand who at least had a few paying gigs to offer. With added piano

from John Potter to fill out the sound, Heinz had found himself

a backing band.

For the Feelgoods the pinnacle of the Heinz days was undoubtedly

the 1972 Wembley Rock’n’Roll Festival, whose bill included

names like Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley. And even

though the cavernous football stadium was still slowly filling up,

it was by far the biggest venue they had played. Wilko even managed

to get Chuck to autograph his Telecaster.

After splitting from Heinz, the band continued on the local circuit

they’d been working for the past year or so, but when pub-rock

began as a reaction t the progressive rock boom, a small but thriving

circuit became established. So it was that in the summer of '73

Dr Felgood loaded up their Transit and headed up the A13 bound for

the capital.

Unfashionable

The Feelgoods were marked out

right from the start -not only because they were playing rather

unfashionable R&B music as opposed to the country-rock favoured

by their contemporaries, but also because they jut looked and acted

more aggressively. Figure recalls that "Lee

developed a much meaner attitude on stage, and one night Wilko started

to skit about on stage in overdrive - the reaction to that was quite

incredible."

For fellow Southender Will Birch of the Kursaal Flyers, it was the

overall look and attitude of the bad which really did the job. "If

they ha looked like the Pretty things or the Grease Band it wouldn’t

have happened because the music by itself wasn’t distinctive

enough. Their impact was that… they presented some familiar

music in a way that was totally new."

Wilko adds : "When things started

happening I’d start to think that what we were doing was a

bit of a crusade, thinking about some of the crap that was going

on at the time like Emerson Lake and Palmer… it felt a bit

like we were trying to destroy all that."

By early 1974, people were starting to be turned away from gigs,

and when DJ Bob Harris invited the Feelgoods to record a session,

this acted as a spur to Wilko to produce songs : "We

did 'She Does It Right', and I seem to recall writing it the night

before. I realised that if something was going to happen we were

going to need original material."

United Aritsts signed the band, but not all of the label’s

executives were happy that their first album, "Down By The

Jetty", was to be pressed in mono. Wilko : "When

we were mixing it we were doing it in stero and I was ending up

on one side with Sparko on the other. A lot of the mixes just sounded

better if everything was placed in the middle. I remember saying

don’t write 'mono' on the sleeve because it doesn’t

matter, nobody will know : we were just trying to make the band

sound right."

When "Down By The Jetty" was released in January 1975

NME doyen Nick Kent seized on the reference points with relish.

"Here is a band", he crowed, "who

on anything approaching a good night can muster a ferocity so downright

devastating it grabs you by the lapels, pins you to the walls with

its breath and screams out "This is Rock and Roll."

While the LP hit the high streets, the Feelgoods found themselves

back out on the road as part of a rare experiment in record-company

co-operation. The Naughty Rhythms tour, featuring Dr Feelgood, Kokomo

and Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers, harked back tp those 60s-style

package tours in an attempt to break three of pub-rock’s bigger

acts to a nationwide audience.

The second album was again recorded with a little overdubbing as

possible and featured several Johnson classics such as "Back

In the Night" and "Going Back Home", the latter co-written

with his long-time hero Mick Green. It also featured Lee’s

highly untechnical but very effective slide playing, which wailed

throughout a cracking version of Muddy Waters’ "Rolling

And Tumbling". Track nine was the appropriately named "Riot

In cell Block No. 9" by Leiber and Stoller - a show-stop-ping

feature of the live act. The LP was received more enthusiastically

than "Jetty" while a single, "Back In The Night",

spread the message further afield.

Wilko was using any off-road time to work on new ideas but the band

were heavily committed to touring in Europe. It was from this position

of weakness that a germ of an idea began to develop. As Figure recalls

it : "There had been this constant

thing in the press about our records which were always 'not quite

good as live'. It seemed like a good idea."

Live shows at Sheffield (May 1975) and the Kursaal in Southend (November

1975) had already been recorded, and "Stupidity", released

in September 1976, was marketed as if it were a brand new set of

songs. In addition, the first 20.000 copies contained a free single

of "Riot In Cell Block No 9" / "Johnny B. Goode".

But the time the record charted it seemed as if every record shop

in Britain boasted a huge reproduction of the classic Lee/Wilko

cover shot in their window - and the following week saw the album

hit No. 1.

RED-HOT

It was to be the Feelgoods’

crowning moment. Yet the massive success of "Stupidity"

- a release designed to take some pressure off the band - only served

to pile it on again. Charles Shaar Murray’s red-hot review

had contained a prophetic sting in its tale when he asked : "The

only worry is where do the Feelgoods go after this ?"

After hitting the top spot, anything less could be seen as a failure.

In addition America couldn’t simply be ignored. CBS had released

"Malpractice" as their debut disc, but had decided against

"Stupidity" as it was felt to be so uniquely English.

The studio chosen for the follow-up was Rockfield, where the band

had worked on "Jetty". But as recording approached, the

pressure on Wilko built up as he desperately worked to preplan songs

to take down to Wales : "I

was writing songs right up until the sessions started. I would stay

awake for two or three days doing songs and crashing out."

Matters came to a head over the inclusion of a Lew Lewis song, "Lucky

Seven", to bulk up the album, and the dissenting guitarist

parted company from the rest of the band. Wilko signed to Virgin,

where he’d record an album with his Solid Senders, before

charting his own course, gigging constantly and releasing albums

through a series of indie labels. Since 1985 he’s fronted

an impressive three piece consisting of ex-Blockheads bassist Norman

Watt-Roy (whom he’d encountered when temporarily replacing

Chaz Jankel in Ian Dury’s band) and Italian drummer Salvatore

Raimundo.

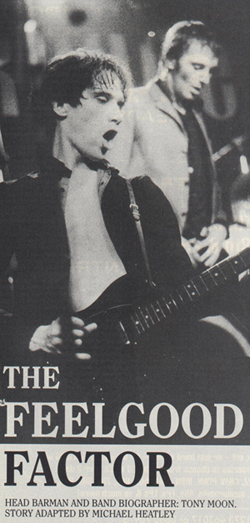

Dr Feelgood pictured at theur mid-70s peak. That's guitarist Wilko

'Necky' Johnson (far left) and singer Lee Brilleaux (second from

right).

John Mayo was the man who had

to step into Wilko’s formidable shoes on a full-time basis.

American singer George Hatcher introduced Mayo, a self-confessed

Peter Green fan, to Lee, who’d straightaway been impressed:

"He’s got an amazing

way of playing : he can play the bass notes and make rhythm while

his other fingers pick out the tune, so a real lot is going on in

his department to fill the sound out a little. In the same way that

Wilko had that chopping style, John’s way is different but

it does the same job."

If ‘Gypie’, as he was rechristened by Brilleaux, had

any lingering doubts about his role in the group, it was over songwriting:

"I can come up with musical

ideas, but I don’t sit down and write songs."

With this in mind, - Nick Lowe, a singer-songwriter who had made

a name for himself as producer of Elvis Costello and the Dammed,

was the choice to oversee "Be Seeing You", the title a

reference to the resurgent 60s cult television programme ‘The

Prisoner’. The late-’77 Feelgoods had grown away from

the earlier beat-boom approach as pioneered by Wilko in favour of

a fuller, more rounded, bluesier sound.

The band had re-signed with UA and were due to go back into the

studio with house producer Martin Rushent. But he fell ill with

hepatitis before the LP could be completed and American Richard

Gottehrer, who’d produced albums by Richard Hell and Blondie,

stepped into the breach.

The resulting "Private Practice" contained at least two

classics: a Mickey Jupp original, "Down At The Doctors",

and "Milk And Alcohol", a chunky-sounding riff from Mayo

with words by Nick Lowe. "They

phoned me up and said we’ve got this great backing track,"

he recalls. “Lee had something of a tune which he had been

singing over it, but no lyrics. So I just went down to the studio

and did it."

The song was the obvious choice as a single and was released in

January 1979, pressed on different coloured vinyls and put in a

sleeve based on a bottle of the alcoholic tipple Kahlua. The record

started to pick up airplay and quickly charted. Suddenly, Dr Feelgood

were in demand again. The follow-up, a re-recorded version of "As

Long As The Price is Right", had rather less impact, stalling

at No. 40.

Having pursued a relentless touring schedule for the past year,

the band elected to keep things simple and make their next LP live.

Once again, Vic Maile put two shows down on tape, the resulting

"As it Happens" slipping easily and undramatically into

the racks in June 1979. Unlike "Stupidity", it wasn’t

going to change the world, despite a free live "Encore EP"

featuring "Riot In Cell Block No. 9", "The Blues

Had A Baby And They Named It Rock’n’Roll", "Lights

Out" and "“Great Ball Of Fire".

The record company were still very keen to have something with the

odd hit single on it and the seasoned Mike Vernon, the man who’d

produced Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall and Focus, was in charge for

"Let It Roll", the Feelgoods’ sixth studio LP. The

album, its cover featuring each member in the form of a foaming

Toby jug, was well received, though it failed to deliver another

"Milk And Alcohol".

REUNITED

By 1980, Dr Feelgood celebrated

an eighth successful year together with "A Case Of The Shakes",

which reunited them with producer Nick Lowe and was what Gypie refers

to as "a real Feelgood album".

Songwriters who included Larry Wallis and former Brinsley Schwarz

keyboard player Bob Andrews, not to mention Lowe himself, made this

the band’s most accessible and "poppy" album. But

Mayo, in particular, was beginning to feel dissatisfied with what

he regarded as the restriction of R&B music.

Both Figure and Sparko had started to feel an urge to quit touring

for a while and enjoy the fruits of their success. As Sparko recalls,

the constant touring "made

you feel as if you were in the army, always being told where and

when to go somewhere". Figure similarly

likens it to being a "biscuit salesman, forever out on the

road selling".

Behind the scenes, Andrew Lauder had left to form Radar, United

Artists had been bought by EMI and the Feelgoods found themselves

on a label where there was little interest in them. The band elected

once again to "play the live

card" and get out. "On The Job"

was the last Dr Feelgood album for a major label - and also the

last to feature Gypie Mayo, whose guitar playing and personality

had revitalised the band for so many years.

Among those who turned up to audition as replacement was a young

guitarist called Gordon Russell, who was edged out by the experienced

Johnny Guitar. But the ex-Count Bishop walked into a situation that

was rapidly deteriorating. Internal pressures within the band started

to reflect onstage, shows began to lose their sparkle and people

began to "go through the motions"

- the antithesis of what Dr Feelgood were all about. When Sparko

decided to depart, Figure felt it would be an opportune moment for

him to stand down too.

With this scenario rapidly developing, the band had secured a one-off

deal with Chiswick. Once again a familiar pattern emerged, as Johnny

recalls : "I’d just joined

the band, it was time to make a record and all eyes looked to me

..." Songs such as "Rat Race"

came with Johnny supplying a catchy lick and Lee improvising a lyric

to fit. The album, entitled "Fast Women And Slow Horses",

was recorded

in June 1982, again with old mate Vic Maile but in Johnny’s

words, "It wasn’t fun

anymore". With that in mind, Lee

and Chris decided for the first time in ten years to pull band off

the road and take a break.

Lee would often go over to the Zero club at Southend Airport where

local musicians would turn up and jam. A regular visitor to catch

his eye was former bass-playing schoolmate Phil Mitchell, while

Gordon Russell, the young guitarist who had impressed at the previous

auditions, was tempted away from Geno Washington. As for a drummer,

Phil Mitchell suggested Lee look up Kevin Morris who, having cut

his teeth on packstage tours in the early 1970s with the likes of

Sam and Dave and Edwin Starr, was currently occupying the stool

in a French heavy metal band called Trust.

ACT

With a totally new line-up,

Lee realized that it was make or break - the band were no longer

the headline act they had once been and if they fell apart again

it really could be over. And as no one, it seemed, was going to

off'er them anything on a long-term basis, Chris and Lee elected

to finance their next recording project, "Doctor’s Orders",

them-selves with Mike Vernon re-engaged as producer. Its release

via Demon was followed by "Mad Man Blues", a mini-album

of blues classics originally issued on the ID label in France. An

early mispressing included "Don’t Start Me Talking"

instead of "My Babe", but a French edition on Lolita with

bonus tracks would become definitive.

Both "Doctor’s Orders" and the extended "Mad

Man Blues" eventually ended up on the band’s own Grand

label (named after Lee’s favourite local hostelry, the Grand

Hotel), which also in time licensed back the classic EMI material.

Yet the next two albums, "Brilleaux” and "Classic",

would emerge on Stiff during its short-lived renaissance. Both were

very polished, very 1980s records which buried the Feelgoods under

layers of production and, as Gordon Russell says, "just

weren’t like we sounded".

In typical Stiff style, initial copies of the first single "Don’t

Wait Up" came shrink-wrapped with a free pairing of "Back

In The Night"/"Milk And Alcohol", while the June

1987 release of "Hunting Shooting Fishing" coincided with

a cassette-only "Crash Your Car Megamix" of several Feelgood

tracks.

Yet again, line-up changes were in the works. A family tragedy forced

Gordon Russell’s retirement from the road, with Steve Walwyn

- whose Midlands-based band the DTs had supported Feelgood on several

occasions - slotting in. His first high-profile gig at the Town

and Country Club turned out well enough to come out as "Live

In London", andwas hotly pursued by "Primo", its

Will Birch produced successor. It was midway through those sessions

that a road-weary Phil Mitchell decided to leave. His full-time

replacement was Dave Bronze, a well-regarded session player who

lived just round the corner in Leigh-on-Sea.

While recording "Primo", Lee started to display the first

symptoms of the cancer which was to claim his life. Towards the

end of the year, Dave Bronze recalls Lee coming offstage after a

high-octane gig with a temperature of a hundred and ten. Midway

though sessions for "The Feelgood Factor", Lee was called

away to London, where he received the news that was to confirm his

rapidly-deteriorating health.

Then came a stroke of luck. Chris Fenwick’s property-developer

brother Brian, 'Chalkie' to his friends, had acquired the Oyster

Fleet, the run-down drinking house in which the original South Side

Jug Band had cut their teeth. Chalkie made his brother an offer

he couldn’t refuse - to take it on as a going concern until

he could develop the site.

The band set about transforming the pub into the Dr Feelgood Music

Bar, with help from Sparko, and doors opened for business in September

1993. Dave Bronze and Gypie Mayo cropped up in reggae favourites

Elvis Da Costa and his Impostors, while the Big Figure appeared,

again with Gypie, in the Shadows cover outfit the Six O’clock

Shadows. Both Figure and Sparko were to become fixtures in the bar,

regarding it as simply "our

kind of place".

CAUTION

It was at Christmas 1993 that

Lee pulled Chris to one side and told him that he wanted to record

a couple of Dr Feelgood gigs at the music bar. Fenwick greeted the

idea with caution: the band hadn’t played together for nearly

a year. But then Lee Brilleaux wasn’t the sort of man you

said no to.

On the nights of 24th and 25th January 1994, Brilleaux and Dr Feelgood

played what was to be their last engagement together. The set performed

on those nights included a new cover : "Road Runner",

the Holland-Dozier-Holland classic which Lee had specifically requested

they play. The song’s lyrics, which feature the immortal lines,

"I live the life I love and

I love the life I live", could, it

seemed, have been Lee Brilleaux’s CV.

In a very short time, the singer’s strength failed dramatically

and on 7th April 1994 Lee Brilleaux died, attended by his wife Shirley

and their two children, Nicholas and Kelly. He was 41 years old

and the big adventure that Lee had embraced with open arms was suddenly

over.

Since the death of singer Lee Brilleaux in January 1994, Dr Feelgood

have soldiered on, keeping the original band's spirit alive.

There was still the sound of

music in the air, though, as on 10th May, which would have been

Lee’s 42nd birthday, the first of what was to be an annual

event took place - the Lee Brilleaux Memorial Concert. Among those

at the Feelgood Music Bar was a Dr Feelgood line-up of Wilko, Sparko

and Figure together for the first time in many years.

To coincide, the live record of Lee’s last gig, entitled "Down

At The Doctors" was released. Shortly after this, in early

July, the Dr Feelgood Music Bar finally closed its doors and the

bulldozers moved in. Next came a valedictory box set of Dr Feelgood

music on EMI, a definitive 104-track compilation which was to draw

a line under Lee’s recording career.

After a year had elapsed, Chris Fenwick slowly started to pick up

the pieces and move forward. No one from the final Feelgoods line-up

had remotely considered the possibility of ever playing together

again other than in the context of an annual memorial gig. Yet time

really is a great healer, and many people who loved the band, fans

and promoters alike, started to ask the same question - "Are

you getting a new singer in ?"

Kevin recalled a prophetic conversation some years before in which

Lee explicitly said : "If anything

happens to me, speak to Wilko". It

was as if, despite all their differences, Lee still regarded the

guitarist as a custodian of the Feelgood flame. With this in mind,

Kevin spoke to Wilko in general terms about the project, but he

was firmly established in his own successful solo career. Other

considerations involved Sparko and Figure, who were occasionally

going out as the Practice with Gypie Mayo.

Finally, the thought emerged that if anyone should give it a go

then it should be the nucleus of the last official line-up. Kevin

spoke to Steve Walwyn about the proposal, and two things convinced

him it was right to consider going on: "I

think Lee would have liked it, and also I think a genuine fan would

prefer to have a band playing Feelgood songs as opposed to nothing."

Phil Mitchell was also contacted.

With the word out on the street, a new name cropped up through a

friend of Kevin Morris. The singer’s name was Pete Gage, a

charismatic blues singer who’d been working the semi-pro circuit

for several years. Gage had a lineage that stretched back into the

early 1960s when he was "a

serious mod" popping pills on a Saturday

night and going down to the Flamingo club in Soho every weekend.

Pete’s big break had come in 1966, when a band he was singing

in had supported Jimi Hendrix at a gig in London’s East End.

In the audience that night was legendary bassist Jet Harris, formerly

of the Shadows, who was putting a band together. He liked the sound

of Pete’s voice, and so it was that Pete found himself recording

a Reg Presley original for the Fontana label called "My Lady".

Harris’s group had something of a jazzy feel to it, a touch

of Booker T and the MGs mixed with a dash of Howard Tate. As Pete

now says of those formative days, "I

wore a suit back then, Jet was very showbiz-minded. I was 20 and

having a ball."

The band didn’t prove to be a long-term affair and Pete eventually

returned to the-semi-pro circuit while he trained to become a psychiatric

nurse and eventually moved to Bristol.

Phil Mitchell, recalling the audition, says that "When

we played 'Back In The Night' it suddenly sounded like us again.

Pete really stood out." Additionally,

as Pete was older than the other auditionees, he lent the proceedings

a certain gravitas a young gunslinger simply couldn’t muster.

Phil : "We had no intention

of ever getting a Brilleaux clone in. We said to Pete do your own

thing, sing the songs your way."

Which is exactly what he did.

To press a new footprint into the cement, the band decided to record

a new studio album, collecting together a selection of suitable

covers spiced up with originals from Walwyn and Bronze. Tracks such

as Peter Green’s "World Keeps Turning", which would

have seemed out of place before, were deliberately picked as they

suited Pete’s bluesier voice and the number duly established

itself as a feature of the live act. The resulting album was given

the title "On The Road Again" to mark the band’s

full-time return to the gig circuit.

Chris Fenwick had reassured contacts with agents across Europe and

dates were gradually being slotted in once again. In May 1996, the

Third Memorial Concert at the Grand saw Pete Gage formally intro-

duced and another bridge in the transitional process had been crossed.

Dr Feelgood were back on the road. And that, in this 25th year of

their existence, is where you’ll find them today with a book

and a double "Twenty Five Years Of Dr. Feelgood" CD out

this month to celebrate the silver anniversary.

|